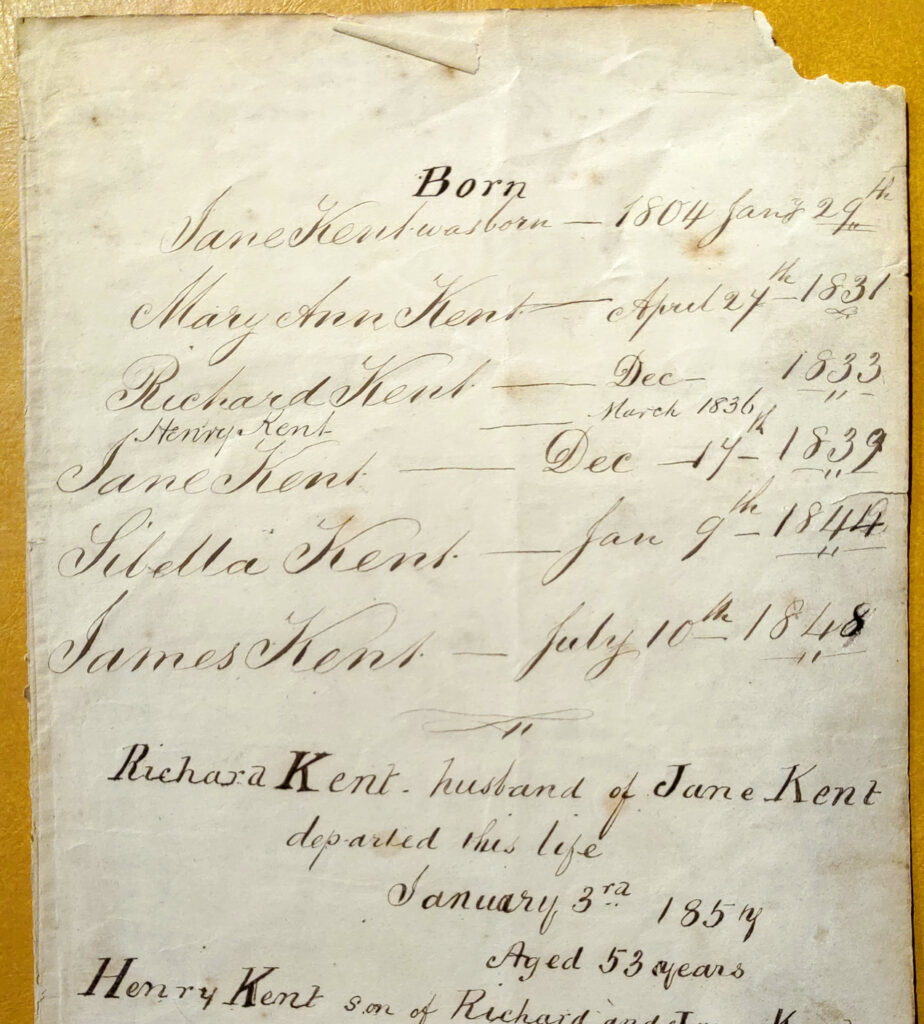

The story of the Eddowes family begins with the family bible. This book was a bought by Joseph Goodman, who was baptised on 2nd February 1798 at the church of St. Gluvias the Martyr in Cornwall, and some of its pages, adorned with beautiful cursive script, are still in the family.

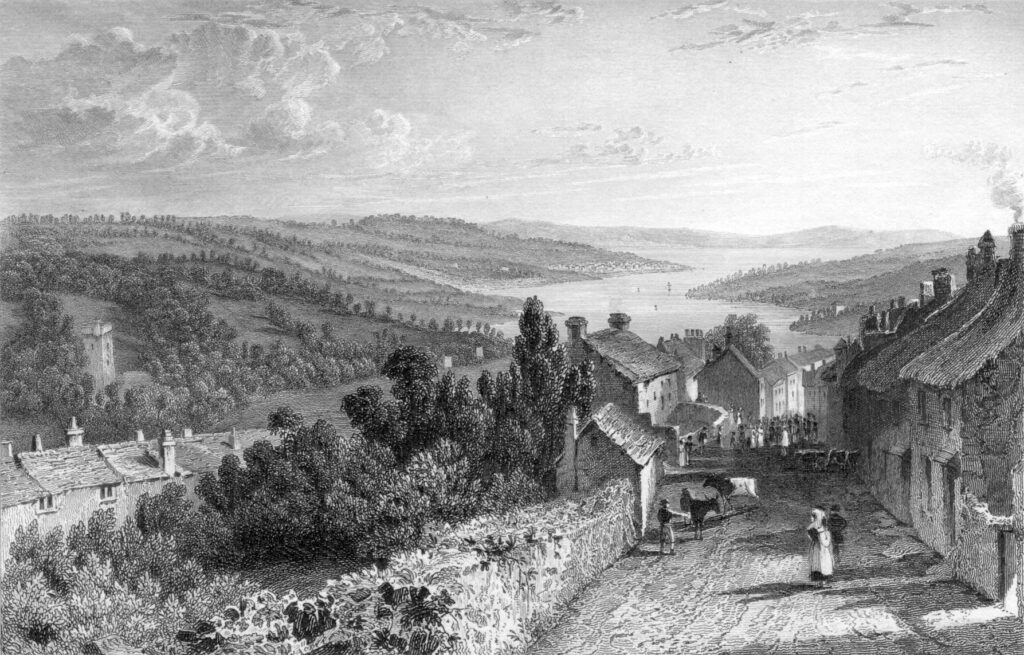

All the Goodman ancestors were born, married and died in Cornwall, mostly in the area around Falmouth. They had a variety of jobs like milling, candle-making, curing leather, and dealing in potatoes. Many of the women did not learn to write, signing their marriage certificates with a cross.

There is a family legend, passed down by Muriel Eddowes, that the Goodmans held a tea party for Charles Wesley, the founder of the Methodist movement, when he was preaching in Cornwall. There’s no mention of this in his diaries but Wesley certainly did preach in their village of Penryn in 1744, so it’s quite plausible.

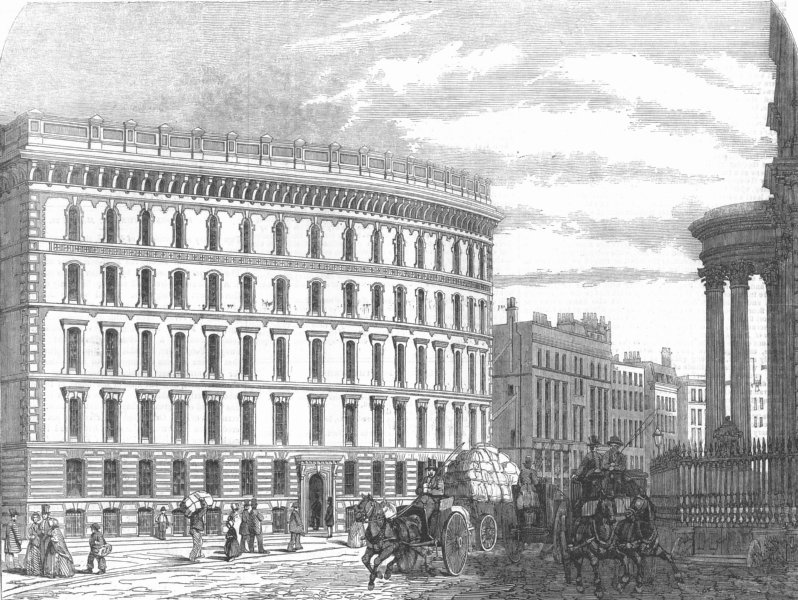

Joseph Goodman, who bought the family bible, had a granddaughter Elizabeth, who made a match with somewhat wealthier stock. The records show that Elizabeth’s father-in-law, James Kent, was an annuitant, i.e. living off an inheritance. Nonetheless, perhaps because James had four older siblings the young James was sent to London at 14 to be apprenticed to a drapery firm. James arrived at Cook and Sons in 1862, working as a porter and living at their warehouse directly opposite St Paul’s cathedral. He was paid in food and shelter, and slept under the warehouse counters.

James and Elizabeth likely met at school in Falmouth. They married at the Methodist Chapel there in September 1871 and then left Cornwall forever, making a new life in North London. Work in Cornwall was scarce and some of their cousins went even further afield, emigrating to America. Leaving home was a path millions of rural English folk trod in the 19th century.

The family bible travelled to London too. Joseph gave the bible to Elizabeth, his Granddaughter, perhaps as a wedding gift. Elizabeth, known as “the boss” of the family, kept detailed records in its pages, including the exact time each child was born.

From sleeping on Warehouse floors James worked his way up at Cook, Son & Co. and by retirement he was a director of the company. His success bought them a home in the fashionable suburb of Winchmore Hill and a second home in Raleigh, Essex. They even had enough to spare to help their daughter Ethel buy her own home “as a wedding present”, and they employed a live-in housemaid, Maud, who was paid “30 shillings a week plus food and uniform”.

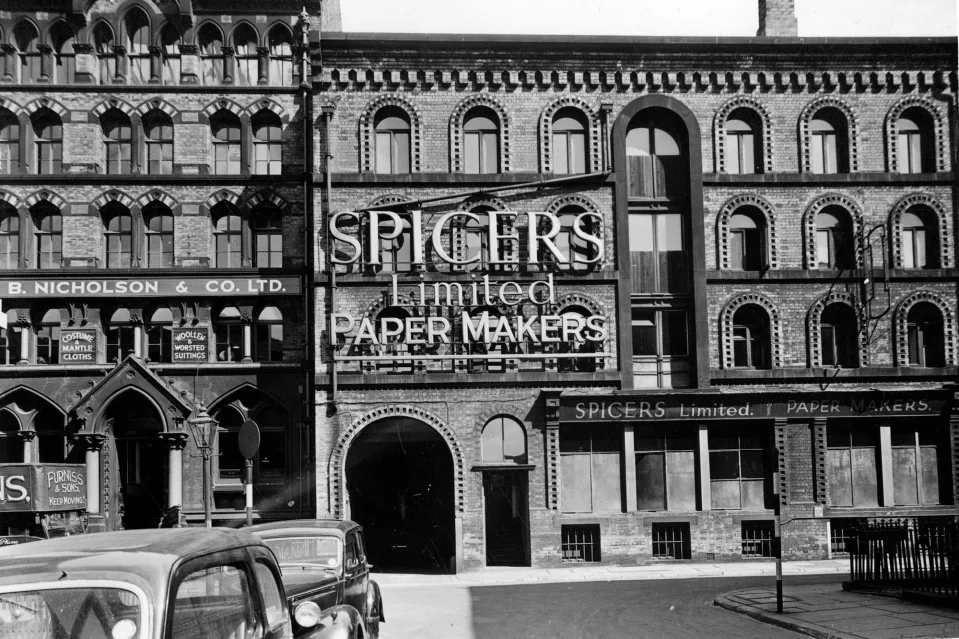

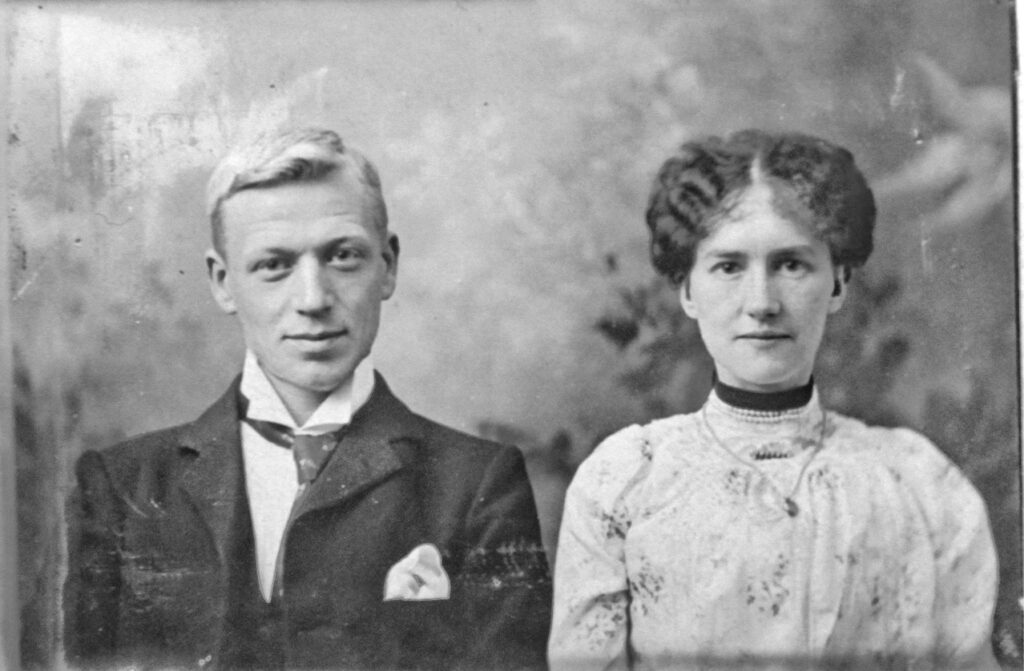

Elizabeth and James’s first daughter, Minnie, was prevented from taking a job. Instead expected to “stay at home and keep house.” Their youngest daughter, Ethel, however, did go out to work becoming one of the first women clerks at the papermaking company Spicers. Ethel met and fell in love with a colleague, Charles William Bourdon. Since Charles was a cockney whose mother grew up in in Shoreditch Elizabeth didn’t approve of the match but her father James talked her round and the marriage went ahead.

Unusually, Charles’s family were not newcomers to Victorian London: they were an East End family going back many generations.

Charles’ family came from the ‘Old Nichol’, a notorious slum in Shoreditch, which was home to Charles’ mother Caroline, her parents Thomas and Ruth Baker, Charles’ paternal grandparents William Joseph and Esther Bourdon, and their parents too. Like many of those living in the East End Caroline, Thomas, Ruth, William Joseph and Esther’s families were weavers, although Charles’ great grandfather Phillip also had spells as a violin-string maker and fishmonger.

Phillip’s mother, Jane, died after sustaining injuries from being hit by a brewery truck – an accident that the Coroner’s report tells us also took down a Punch and Judy show. Phillip’s grandfather Daniel Bourdon (Jnr.) was married secretly at London ‘marriage shop‘. When he was born in 1727 London’s population was less than 10% of what it is today.

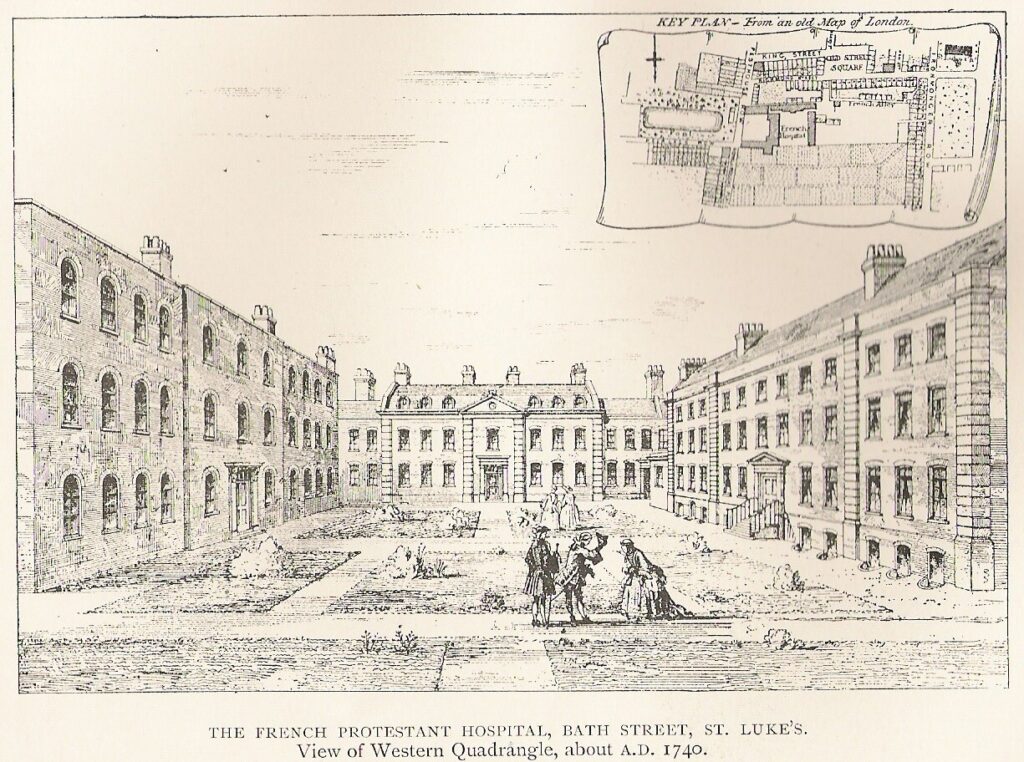

Further in time the trail turns away from the East End, away from England in fact. Daniel (Jnr.) was baptised at the ‘French Church’ on Threadneedle Street, the church where his parents were married, and his father, Daniel Snr., spent the last year of his life being cared for in London’s French Hospital. The hospital was for Huguenots: French religious refugees, and the records show that Daniel Snr. and his parents, Salomon and Marie, were from Croisy, Normandy. We don’t know if Salomon and Marie escaped France, or sent their young son to England on his own to make a new life for himself.

Their story survives thanks to the longevity of their distinctly French surname, Bourdon, and the record keeping of the Huguenot Museum in Kent.

Daniel’s story of escape from France was nearly two centuries old when his Great Great Great Great Grandchild Charles William Bourdon married Ethel Kent at the Wesleyan Methodist Chapel in Finsbury Park, London, 1905.

Once married Charles and Ethel bought a house of their own, helped by Ethel’s parents, Elizabeth and James Kent, on condition that they didn’t live too far away. They had two children, Mary and Muriel.

Muriel became an Eddowes after marriage, a name which appears to be of Nottinghamshire origin.

For much of the middle part of the 19th century George Eddowes lived in the centre of Nottingham with his wife Sarah and four children. He was a solicitor and worked in the practice ‘Wise & Eddowes’ based in rooms round the corner, a profession in which he attempted to apprentice his sons. That apparently didn’t work out, because in later years his son William was running a greengrocers with his wife Anne, of Lincolnshire origin. Their son Walter, around the same time as the Goodmans and Kents were doing in Cornwall, made the jump to migrate to London, where he met his wife Caroline and became a railway clerk, a job his son Richard would take up too.

Richard Eddowes “held a grudge” against his wife Kate on account of the fact that she kept it to herself that she was born out of wedlock. Kate’s father, one John Pavey from Whitechapel, left Kate’s mother Kezia after she was born. What became of him we can’t tell. Kezia went on to marry a man called William from Pembrokeshire (another immigrant to London) and they ran a coffeehouse together not far from the Regent’s Canal. They had two children of their own and Kate lived as one of the family. Apparently Richard only learned of this when he saw his wife’s father’s surname on the marriage certificate.

Richard and Kate had just one surviving child, Ken, who met my Granny, Muriel, in the late 1920s, perhaps on trips to her Cornish Grandparent’s who still lived in Winchmore Hill, around the corner from Ken’s home.

Muriel was certainly attached to the area. She remembered picking violets and primroses on the railway embankment and waving at the train drivers, and eating her first ice cream at a fate in Broomfield Park (she recalled saying to her father Charles: “put it away. I don’t like – it’s cold!”) Her Grandparents’ home had a beautiful garden and Grandma Elizabeth, still very much the “family boss”, would insist on them joining for Christmas dinner. Grandpa James took Muriel to watch the Lord Mayor’s Show pass his office opposite St. Paul’s Cathedral. And Muriel never forgot her Cornish roots, taking holidays there in the years between the wars.

Ken and Muriel went for walks and motorcycle rides together in the countryside around North London. They were active in the same Methodist chapel in Finsbury Park: Muriel running the Sunday school and Ken playing the organ. They organised trips to the country and after they married Ken made the decision they would move to a place they’d first visited on a church day out: Cuffley, Hertfordshire. Together they opened a tea shop, ‘Rovers’, in the village and so left London behind them.

A few pages of the Goodman family bible were kept in Ken and Muriel’s papers. We’re not sure what became of the rest of the book, but the surviving pages are the enough. Their beautiful script is quite striking and those little details held within, such as the exact hour of the night that children were born, have the power to transport you across the centuries. There’s plenty to explore that their pages don’t tell, such as Ken and Muriel’s own story together, but that deserves a space of its own.

*

Text by Ric Lander, October 2023.

Primary sources including census data and parish records can be explored here.

Sections in quotation marks are from interviews with Muriel Eddowes conducted by Pat Lander in August 2004 and earlier.

This article had a first major update on 30th December 2023 correcting errors and adding information from new sources.

*

If you are interested in exploring your family history here are some free and open access sites I would recommend:

- https://www.wikitree.com/ – free site where you can compile your family tree and connect it to others’.

- https://www.freebmd.org.uk/ – records of births, marriages and deaths in England and Wales since 1837.

- https://www.freereg.org.uk/ – parish records of baptism, marriage, and burials in England and Wales up to 1837.

- https://www.freecen.org.uk/ – records of the UK census beginning in 1841 and up to 1911.

Note that the data sets on the above sites is not comprehensive, so you may need to use paid services to fill in the gaps.

Leave a Reply